A few nights ago, on Christmas, 2023, my circumstances rhymed and riffed off of a similar night a little under a decade ago, improvised by the jazz of life, like jazz, seemingly haphazard and slapdash yet structured, written or unwritten ahead of time, on time, in time. March 1st was a frigid day in 2014, and I was in a different city, in Chicago. As I did on the night of Christmas, 2023, I’d taken a commuter train into the city alone to see a Miyazaki film.

The Wind Rises was supposed to be Hayao Miyazaki’s last film. I remember making a big deal about just how much The Wind Rises was about real life. It doesn’t take much critical thinking or media literacy to figure out most all of Miyazaki’s films comment on real life issues and concerns, and yet The Wind Rises was a biopic of sorts; it was directly adapting and embellishing the life of a person who walked this earth once upon a time, drawing parallel lines between the Japanese World War II fighter plane engineer Jiro Horikoshi’s life and the people in Miyazaki’s life like his mother and father, the latter also a director of a manufactory for Japanese fighter planes.

I’d seen almost every film he’d made up until this point, and a bunch from Studio Ghilbi as well, films like Whisper of the Heart by the tragically short-lived Yoshifumi Kondō, and several films like Grave of the Fireflies, Only Yesterday, and later that year The Tale of Princess Kaguya by Ghibli’s late lesser-known titan, Isao Takahata. I’d often create a loose (honestly reductive) dichotomy between Miyazaki and Takahata. Whenever I talked about the films of these two masters and compared their works, I’d usually talk about Takahata’s inclination toward varying animation techniques and aesthetics to tell stories of grounded topics, and juxtapose that with Miyazaki’s firmer house style, paradoxically filled with whimsy and fantastical sprites and monsters and lush landscapes. I loved their works each in their own way; taken together as a whole, they are like yin and yang to me, they are two decidedly different yet dialectical, equally essential aspects of the potential and poignancy of animation. With The Wind Rises and The Tale of Princess Kaguya released that same year in 2013, I’d often remark that the two directors had swapped places somewhat; the whimsical one made a war film, and the grounded one painted a gorgeous portrait of a famous Japanese folktale.

Signaling the film’s end, the credits gently and effortlessly rolled up the screen, as gentle and effortless as all of Miyazaki’s films are told. Yumi Matsutoya’s kayōkyoku debut “Hikō-ki Gumo” faded in from the cinema speakers, and I cried not only from of the sheer weight and finality of The Wind Rises as “Hayao Miyazaki’s last film” but because it had felt so fitting and appropriate for the movie to exist as his swansong. It all felt right, The Wind Rises falling into place at the end of the line, in line with Miyazaki’s concerns about war and nationalism and his fixations with beauty found both in nature and in humankind’s inventive spirit, in machinery and aviation.

The L wasn’t running right that night. A snowstorm had come in by the time I came out of the theater. I walked all the way to Ogilvie in the snow to take the train home, my body shivering, mind racing with thoughts about the movie I’d just seen.

***

Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka, localized as The Boy and the Heron in English, was supposed to be Miyazaki’s last film. The first thing the moviegoer sees after the comforting sky-blue Studio Ghibli title card is an air raid siren against a charcoal-black sky. Twelve-year old Mahito awakens to one of the many Tokyo air raids that ravaged Japan in the Pacific theater of World War II. His father Shoichi tells him that the nearby hospital is on fire. His mother is there. Mahito darts toward the fire in a frenzy, his face grotesquely twisting and morphing as he jostles his way past expressionistic, horrific Edvard Munchesque muddy blurs of human beings in a mind-blowing sequence. He finds the hospital burning down before his very eyes. It’s intense, precise in its bleakness, and virtuosic in a way that somehow feels more exacting and humbling than indulgent.

In a bizarre stroke of marketing, marketing for the film was nonexistent in Japan, and the only thing Japanese viewers saw of the movie before the movie itself was the poster, released on December 13th, 2022. A delicately colored sketch of a grey heron, eyes peeking out between its beak, the Japanese title a question, a confrontation in striking bright red against a white coat of feathers. I was intrigued by this bold, decidedly sparse single article of advertising, this conscious decision to let the film speak for itself, and I made one myself: to try my best to honor that approach while I awaited the film’s release in America. I suppose the international distributor had other plans; their marketing campaign was much more about “[giving] people just a taste that this is going to be a Miyazaki film unlike what they’ve seen before,” presenting trailers with flashes of some of the film’s more eye-catching moments before it was even released stateside, to my frustration but frankly not to my surprise. One of my roommates and I discussed how the trailers felt like somewhat of a misdirection on distributor GKIDS’ part; at one point she said the trailers “made the movie look like Spirited Away.”

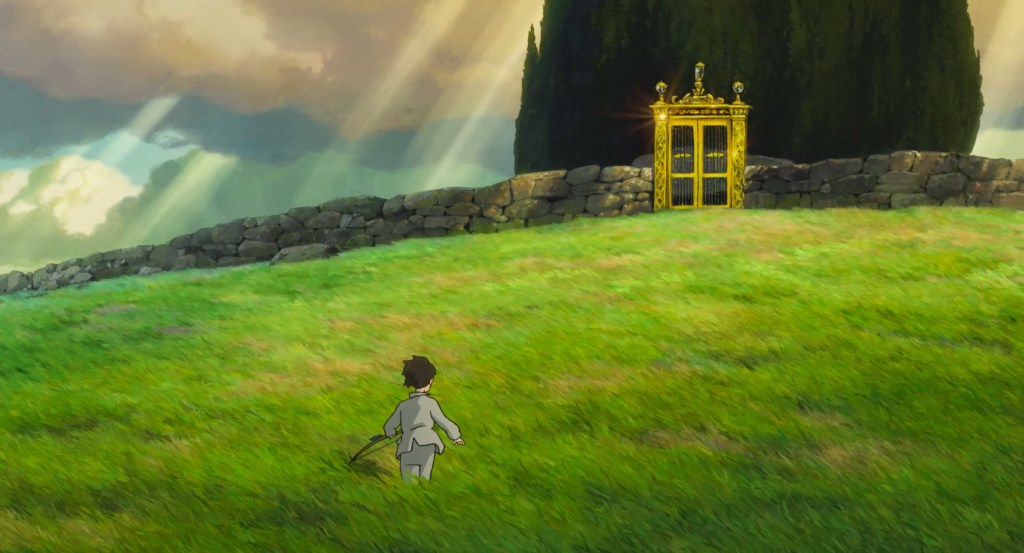

And the movie is like Spirited Away somewhat; as you’d expect, there’s always a decent amount of overlap between all of Miyazaki’s films. Like My Neighbor Totoro, The Boy and the Heron involves a young child leaving Tokyo with their family and moving somewhere more remote, to the inaka (田舎) or the Japanese countryside. Stories involving people from Tokyo going to the inaka are a genre unto itself, and it certainly isn’t unfamiliar territory for Studio Ghibli. Again, My Neighbor Totoro comes to mind, but there’s also Takahata’s Only Yesterday, which follows Taeko, a 27-year old woman from Tokyo, taking vacation days from work to travel to the inaka to work in the safflower fields and live there as a passionate curiosity, finding herself reminiscing about her childhood, her reflections rippling back to the present. Gravely, in The Boy and the Heron, Mahito’s family travels to the inaka not as a vacation, but out of obligation and evacuation. I couldn’t help noticing Mahito’s aunt and future mother Natsuko’s home is so Western in its design compared to the rest of the estate, but the setup feels familiar, a suggestion of a callback here and there to his older films, yet not quite. Like Spirited Away, the child stumbles upon another world separate from their reality. In that movie, Chihiro is thrust into the spirit world minutes into the film with the help of Haku, but the lead up to Mahito stepping through the threshold into another world is a slow burn, filled with moody transitions and bolder cuts that question the viewer’s grasp on what’s real. The heron ominously pesters and beckons Mahito, growing paradoxically more anthropomorphic and monstrous, toward the other world suffused with beauty, whimsy, and imagination.

As I mentioned before, the distributor also decided to localize the name of the film as The Boy and the Heron. Localizing titles of films from one language to the other by changing it to something else (that is, not directly translating the title) is standard practice and nothing new to film let alone any sort of media. One of my favorite films, In the Mood for Love, isn’t remotely titled that in its original Chinese: Hua Yang Nian Hua (花樣年華) or “the age of blossoms;” the only similarity is they’re both titles of songs. When it comes to Ghibli films and especially Miyazaki’s films, most of the titles are localized pretty faithfully. Spirited Away is Sen to Chihiro no Kamikakushi (千と千尋の神隠し) in Japanese, literally “Sen and Chihiro’s Spiriting Away.” Nausicaä’s English title is so faithful that it ends up sounding awkward in English. Princess Mononoke from Mononoke-hime, Kiki’s Delivery Service from Majo no Takkyūbin (“Witch’s Express Home Delivery Service”), most of Miyazaki’s titles in English are as literal as it gets. I take issue with Takahata’s Omoide Poro Poro (おもいでぽろぽろ, literally, “memories tumbling down” or perhaps “memories pouring down”) being localized as Only Yesterday if I’m being completely honest—it takes away the onomatopoeic quality of the Japanese and opts for a turn of phrase instead—but I understand the decision; localization and translation aren’t simple tasks. That said, I kind of wish they kept the original title intact for this film this time.

Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka, or How Do You Live? refers to the title of a 1937 novel by Genzaburo Yoshino, though the film only loosely takes on some elements of the novel. Like The Wind Rises, Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka is actually a composite of multiple works and concepts, rather than a straightforward adaptation. There’s a metatextual quality to these later works of Miyazaki’s that’s fascinating to me. Any enormous fan of Howl’s Moving Castle (so like, a gigantic portion of Ghibli’s fanbase) knows that Howl’s Moving Castle is such a loose adaptation that it’s blatantly its own work, even more so than most adaptations usually have to be. Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka and The Wind Rises operate quite differently from even that example. The Wind Rises, named after a 1936 novel of the same name by Tatsuo Hori, takes elements from said novel and blends it with vignettes and sketches from the life of Jiro Horikoshi, directly refers to Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain constantly, all the while delicately drawing comparisons between all of this and Miyazaki’s own life.

Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka in turn uses its title to suggest similarities between the 1937 novel and the film—indeed, the film’s protagonist, twelve-year old Mahito, is supposed to be loosely based on the one from the novel. In reality, much of Mahito’s characterization stems from Miyazaki’s personal experiences as a young boy and his relationships with his parents. The phrase “Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka,” or “How Do You Live?” is in fact a question directly posed toward its own characters, and in turn the audience itself. We lose this dimension of the film’s title by calling it something as plain and matter-of-fact as The Boy and the Heron. I mentioned being bothered by Only Yesterday as a title earlier but I definitely understand shifting away from the original title there; we English speakers don’t exactly have a vocabulary or cultural contract to use onomatopoeia naturally in everyday speech unless we were trying real hard to sound like absolute clowns. But Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka, that’s just a question. Not only that, it’s an interesting, unanswered question. And you can translate it pretty literally for the most part. The only thing that might be a little awkward is the fact that kimitachi is specifically a plural “you;” say what you want about The Boy and the Heron as a fitting title, but I’m pretty sure we dodged a bullet when GKIDS decided to scrap plans to distribute Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka in the West as How Do Y’all Live?

***

While I was studying for my bachelor’s at Wheaton College in Illinois, I worked as an audio-video tech on campus. Wheaton’s a Christian liberal arts college with a prominent conservatory program, so a lot of the gigs I worked were often specifically recording or attending recitals and concerts with full orchestras, made up of many acquaintances and friends. And so I was introduced to a lot of classical music that I might’ve otherwise never sought out, from the genteel Baroque pieces to the swelling, beautifully dramatic, sometimes unfortunately nationalistic Romantic opuses, to the Modern pieces gesturing toward and eventually embracing the atonal. While I was working as a tech at one of these concerts one year—hell, it could’ve been the same year I went to see The Wind Rises—there was a piece that lodged into my brain for a while. It was frankly a little hard to ignore, as the orchestra itself had to shuffle around a little bit and rearrange itself for the performance. Written by Charles Ives in 1908 and revised in the 1930s, “The Unanswered Question” involves a lush, slow and sustained string arrangement from the orchestra, a trumpet repeating a stoic, slightly off-kilter five-note phrase at intervals, and a set of woodwinds responding to that phrase, progressively louder and shriller and dissonant. In the performance I attended, the solo trumpet was off-stage, perhaps stage left, I don’t quite remember. All I remember was the music itself communicating to me, even without the program, that the trumpet was posing that “Unanswered Question,” “The Perennial Question of Existence” as Ives calls it, against the backdrop of the strings. I remember the woodwinds conspiring and struggling to provide an answer, their dissonance illustrating perhaps the vanity in attempting to answer such a question. As a doubtful, newly agnostic student at a Christian liberal arts college, you tended to come across that question often; I knew it all too well.

***

Mahito has a bit of an edge to him compared to other Miyazaki protagonists. After getting into a fight and getting beaten down by local children, Mahito gashes the side of his head with a rock on his way home. All of us in the theater audibly gasped, first at the sight of so much blood, but then at the notion that someone written by Miyazaki would even think to do something so brazen; presumably the plan was to frame one of the children with the deed. This is all shown with such quiet stoicism, in silent montage set to Joe Hisaishi’s decidedly modern, minimal score. Mahito’s father Shoichi, eyes practically bulging with lunatic vengefulness, demands from him the culprit of such violence, but Mahito doesn’t accuse anyone of this, and instead claims it was an accident. There’s a nuance and naturalism to how Mahito is characterized as a young boy with schemes and changes-of-plans-and-hearts, with contradictions and complexities. This isn’t to say that Miyazaki’s other protagonists, Ashitaka and Chihiro and Kiki and Sophie, to name a few, aren’t flawed characters. But Mahito’s struggle is a much more internal one compared to those that came before him. Here is a boy who lost his mother not too long ago, bitter and alone, expected to accept a woman who looks exactly like her, Natsuko, as his new mother. Here is a boy who hasn’t really the time or faculties really to grieve.

The Boy and the Heron as a title only feels apt for this first stretch of the film’s runtime, as it gestures at an almost literary quality of the rivalry between Mahito and the persistent meddlesome grey heron. Hisaishi had assigned a scarce, three-note motif for the heron, and as the heron becomes more violent in its taunting and goading, the motif gets cut even shorter and louder, mimicking the screeching and squawking of the heron itself. Being excused from school due to his severe injuries, Mahito spends most of his time obsessively finding a means to dispatch the heron, crafting a bow and single arrow out of bamboo, bartering with the estate’s elders, cigarettes in exchange for a sharper knife and other materials. But then the film brings the novel itself to our attention. Mahito stumbles upon the book Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka while makeshift fletching his arrow, finds a note from his late mother Hisako, reads the novel and weeps. It is exactly this moment, when he reads the novel the film is named after, left behind by his beloved mother, a novel about one’s place in the world, how to navigate hardship, how to exist, it’s here that he overhears Natsuko is missing, and seeks out the heron not only for his own vendetta, but out of concern for Natsuko, however tinged with selfishness and self-preservation it may be.

The heron leads Mahito to a mysterious abandoned tower built by Natsuko’s granduncle. When the film first mentions the granduncle, the stranger next to me and I shared a chuckle as we saw an old photo of the granduncle as a young dandy, and the narration said the granduncle was exceptionally intelligent, but “read too many books and went crazy” which is a pretty hilarious line if we’re all being completely honest. I figured it perhaps alluded to Friedrich Nietzsche, having famously gone through a mental breakdown late in his life. Mahito and a cocky elderly housemaid, Kiriko, arrive at his tower, built around a meteorite, its threshold crowned with the Latin “fecemi la divina potestate,” recalling Dante, recalling Inferno:

“Through me the way is to the city dolent;

Through me the way is to eternal dole;

Through me the way among the people lost.

Justice incited my sublime Creator;

Created me divine Omnipotence,

The highest Wisdom and the primal Love.

Before me there were no created things,

Only eterne, and I eternal last.

All hope abandon, ye who enter in!”

Here Miyazaki texturally, metatextually begins to sketch out the film as his very own Divine Comedy of sorts, fast-and-loosely structuring Mahito’s journey through the underworld in search of Natsuko after Dante’s seminal work, even if notions of an afterlife here are sharply distinct from the Inferno, Purgatory and Paradise of Dante’s design. I’m not pointing this out because Miyazaki is secretly adapting The Divine Comedy exactly; I’m not interested in finding these connections to “explain” the film. I just find it interesting that he’s taking our cultural understanding of that work and recontextualizing it; he’s signaling and shifting Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka toward the allegorical much more than his previous works.

The granduncle, shrouded in shadow, commands the heron to be Mahito’s guide, and the heron, Mahito, and Kiriko all sink through the floor. Mahito awakes in the underworld. Somehow, while Spirited Away blatantly involves a realm inhabited by spirits and ghosts, the world of Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka is tinged with this solemn weightiness to it all, it’s so much more bluntly about death, perhaps in a different tradition. Golden hour rays of amber sunlight filtered through dark clouds, wide grassy fields leading to deep evergreens and vacuous dolmens, endless oceans dotted with derelict galleons and skiffs; “expressionistic” once again comes to mind.

Mahito finds his Vergil in both the crafty heron and this world’s version of Kiriko, now a younger masculine seafaring sort, seemingly a different person with no memory of Mahito. He encounters ancient wandering souls, and souls nascent with potential and childlike innocence in the warawara. As I watched the life, death, and rebirth of souls culminate in the sequence introducing Himi, as Himi set both the predatory pelicans and warawara ablaze to allow souls to be born above, I found the totality of it—the warm glow of immolated birds and balloon-like sprites both falling like comets, like downed warplanes, like napalm burning Tokyo, downward to darkness—haunting and beautiful. I found it fitting that a film so preoccupied with the question of existence, set during World War II, has such a Modernist sensibility to it all. Even as the gruesome image of a dying pelican with scorched skin speaking with Mahito flashed grimly on the silverscreen, as they spoke of the displaced pelicans’ desperation for something, anything to sate their hunger, I couldn’t help but think about how Miyazaki seemed just as interested in positioning death itself as something beautiful, as something that spawns beauty.

Himi explains to Mahito the metaphysics of the underworld and its ties to her granduncle’s tower, and I started to wonder: what does it mean for Miyazaki to write a story where he’s essentially hanging out with his mother as a child in the film? A lot of people that I’d spoken to about Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka seem pretty lukewarm about it for whatever reason, and perhaps if I had to guess, there might be something to be said about how long we really get to “hang out” with these characters compared to other films. We only really see Himi introduced for perhaps the last third of the film, and sure, while that makes sense within the context of The Divine Comedy being an influence on its structure, Himi being Mahito’s Beatrice doesn’t really take away from the fact that we don’t really see the two of them spend a lot of time together. It’s a lonely film.

Miyazaki’s mother died in 1983, before Nausicaä in 1984, before Studio Ghibli was formed in 1985. It’s strange, but I realize only now that all this time, after years of watching his films, I hadn’t really considered who would be influences or references for Miyazaki’s characters, and it seems that Miyazaki’s mother Yoshiko had inspired many. The rowdy sky pirate gang leader and mother Dola in Castle in the Sky; the hospitalized, gentle Yasuko in My Neighbor Totoro, her complications mirroring Yoshiko’s own bout with spinal tuberculosis, darkly underpinning the easygoing slice-of-life from the inaka for most of the film; Miyazaki’s own characterization of the determined and faithful Sophie in Howl’s Moving Castle; the grumpy, but ultimately kind-hearted Toki living in the nursing home in Ponyo; tragically, Miyazaki draws a throughline between The Wind Rises’ literary influence and his own life in the creation of Jiro’s love interest, Nahoko, as she suffers and eventually dies of tuberculosis. All of these characters, perhaps many more, have spectres of Yoshiko, from Hayao Miyazaki’s mind to the page to the silver screen. I can see Yoshiko, familiar ghosts of her haunting not only Himi but perhaps even more so in Kiriko’s masculine swagger, and in Natsuko’s frail gentility too. If anything, Himi feels the least like the sort of archetype Miyazaki had laid out for so many of his characters based on his mother up to now. I can’t help wondering if the reason why we don’t spend a lot of time with Himi—why Mahito doesn’t—comes out of this futile, almost childlike desire for an impossible scenario, to spend time with someone dear, to so much as see what they were like, as children.

Himi tells Mahito that Natsuko is being held deep in the meteorite, in a place called the Delivery Room. The Delivery Room is dense with death, ominous paper streamers hanging in circles over a sleeping Natsuko, like sterile lights over a hospital bed, like mobiles over a crib, like talismans warding off evil. Another dolmen rests behind her, an arch, another threshold to blackness, an utter void. Childbirth, strangely yet so obviously a crossroads between life and death. The stone doesn’t want Mahito here, it repels him. Natsuko doesn’t want him here either. The paper envelops them, mummifies them. Writhing in pain, like labor pains, Natsuko lashes out at him, telling him she hates him. Mahito calls out to her, spitting image of the late Hisako, “Mother!” almost as if an accident. Then, an attempt to truly affirm her, Mahito calls out again, “Natsuko! Mother!” For me, this moment was the climax; my eyes transfixed upon the silverscreen, the moment seared itself into my memory. It communicates with such mythic and psychological intensity, the intensity of letting go of all preconceptions of the other, the intensity of letting in another person into your life, in spite of the messiness of it all, against the imposing weight of death itself.

Natsuko, moved or perhaps snapped back to her senses, tells him to run, but the paper overwhelms them, and Mahito is ejected from the Delivery Room. Hisaishi’s score swirls elegiac, a single chord from the piano, the reply of the tolling of a bell, funerial and constant, against a bed of swelling strings. Himi burns the paper and begins to guide Natsuko out of the Delivery Room before the meteorite repels her too, incapacitating her.

The granduncle summons Mahito to his heavenly realm in the tower through a dream. He explains that the source of his power is cosmic in origin and to maintain his world, he must build a tower out of a set of smooth stone toy blocks, set them in teetering balance, and rearrange them everyday. Mahito shares his bloodline, and the granduncle wants him to take his place as the caretaker of the world. Hisaishi’s leitmotif for the granduncle here, steady and expectant notes from a piano and mallets into triumphant chords, strings collecting and building and burgeoning with potential, still working within a more minimal tradition like the rest of his score; it all captures the tired hopefulness residing within the granduncle’s request, potential as limitless and powerful as the ocean that surrounds them. Observing somehow that the stone blocks are “filled with malice,” Mahito says he can’t be the granduncle’s successor. The heron, slapdashedly disguised as a parakeet, frees Mahito from once again being a man-eating parakeet’s dinner, and they follow the Parakeet King and his entourage, having captured Himi, encased in glass.

The Parakeet King rallies his subjects and explains his gambit to use Himi as a bargaining chip with the granduncle, as she and Mahito have committed a taboo entering the Delivery Room. Here, the parakeets have a clearly fascist coding to them, supplemented by Hisaishi’s theme for the parakeets expanded to the tune of a militant march. Apparently, feral parrots and parakeets commonly live in nonnative habitats as a sort of invasive species. Miyazaki and the animators have drawn the Parakeet King particularly as a sort of kaiser, prominently wielding a saber that European rulers and generals would use, and particularly the sort of thing you’d see on a photo or painting of men of such station during and after Japan’s Meiji period. This is all done with a lighthearted yet incisive touch, parakeets hoisting standards and emblems harkening to fascists like Nazi Germany and the Mussolini regime in Italy in World War II, parakeets with sabers, and most hilariously parakeets with signs and boards simply saying “Duch!” on them; it doesn’t mean anything really in any real context really, maybe it’s supposed to be more like “Duke!” but maybe it’s supposed to be pronounced like “Duck!” in this case? Cause they’re also birds?

The Parakeet King and his entourage storm their way into the granduncle’s realm, and the two have a chat over the state of the underworld like politicos. Mahito and Himi reunite, and the granduncle pushes his offer to Mahito again, this time having searched through time and space for stone blocks spotless from malice. Mahito, remembering his scar from his self-inflicted wound earlier, tells the granduncle and acknowledges that he himself is full of malice, but that he has his friends to help with that. The Parakeet King finds the stone blocks and the notion of their importance on the integrity of the underworld asinine and hastily builds a tower on the spot, slicing them in half out of frustration, causing the underworld to collapse. The children and the heron escape with Kiriko and Natsuko, saying goodbye to the granduncle. Mahito warns Himi that she’ll meet a terrible fate, but Himi accepts this and returns to her own time, along with the younger Kiriko. Natsuko and Mahito return to theirs, along with the parakeets and the pelicans, the parakeets reverting to their normal size while the pelicans find themselves in a less hostile habitat.

It’s hard not to see Miyazaki himself in the granduncle here. A wizard crafting beautiful worlds, worlds apart from the oppressive weight of the real. I’d never call Miyazaki’s films “escapist,” and I’m sure Miyazaki himself wouldn’t call them that. Even so, I wonder if maybe Miyazaki finds himself a bit complicit in others’ escapism, thanks to his past films. The balancing of stone toy blocks—platonic and perfect geometric shapes, shaping the fabric of the underworld itself—is such a perfect representation of this childlike creativity and wonder against the responsibilities and “real-life” of adulthood. Rejecting the expectations of his bloodline and refusing the potential of relief and release from worlds detached and apart from our own, Mahito’s return to his own world—ravaged by pain and suffering from a recent world war—represents a radical acceptance of that pain, accepting fellowship with even those unlike him into his life as a means to continue living.

While I was doing some light research to write all this and try to organize my head somewhat, I decided to make a quick glance at the Japanese Wikipedia article for the film because I was curious about some of the terms in the film in English, and wondered how literally they were translated. I think I was specifically looking for “The Delivery Room” and wondering how that was written out in Japanese, and I couldn’t help but notice the plot summary’s final line:「おわり」の表記はない。

Why did the contributor to this article care so much that the words “The End” were nowhere to be found when the film was over? I feel like this echoed a sentiment I heard from some of my friends. One of them told me matter-of-factly that the ending was “unresolved.” I’d imagine the reason why my friend considered the ending of Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka unresolved has something to do with the heron’s final exchange with Mahito. The heron so deftly captures the essence of the casually cynical adult, telling it like it is, telling Mahito that he will forget everything he experienced in that other world, that he should forget. Mahito, still carrying one of the toy blocks, tells the heron that he won’t, even as it seems that the adults around him already have. The final shot of the film stoically presents Mahito, older now, leaving his room in his Western-styled home behind as his family, now a half-sibling larger, moves back to Tokyo.

***

On the night of Christmas, 2023, as the credits rolled, I sat and watched all the names of those who worked on the film, out of reflection and respect. I walked a few blocks over from the theater into Chinatown for dinner. I had some chilled sake with my food. I thought about the film and what it meant to me. I thought about Charles Ives’ “The Unanswered Question.” Unlike the catharsis I felt with The Wind Rises, Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka left me in a morose state of mind. I kept glancing over at the host glancing back at me as I had ramen, I wondered if they were making eyes at me; I felt so utterly lonely and alone. Growing tired, I left cash on the table when I was done eating and walked to North Station, my mind gently swirling from the sake, and took a train home.

The next day after work, I started writing this essay on a whim. I wanted to write something fast and loose, anything at all, resolving to get back into the habit of putting my thoughts to paper. I told myself that I would finish writing it that night; it’s now been two days into the new year. I’ve had an unexpected bout with COVID, and I’ve been struggling to articulate what it is about Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka that left me in that somber mood on Christmas night, my own personal baggage aside.

Thinking about whether or not Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka feels unresolved got me thinking about the general notion of endings themselves. It might be a bit strange to read this or consider this, but what makes an ending like this unresolved and an ending like Spirited Away’s any different? What proof do we have that Chihiro, also carrying a keepsake of her experience, doesn’t simply forget all that she’s learned as she grows into adulthood? In Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka, we have pretty good reasons to believe that Mahito is on the right track, as he packs the titular novel gifted from his late mother into his bag and pulls something out of his pocket, staring at it intently for a while. The film doesn’t offer us a closeup of what it is, but we can assume it’s the same toy block that he’s kept all this time. The film’s outset involves a sort of grave subversion of a vacation to the inaka, and the film’s conclusion has Mahito relocating to Tokyo, Tokyo being such a towering representation of opportunities and of Japan itself culturally that there’s an entire verb, 上京する(joukyousuru), dedicated to “moving to Tokyo” or “moving (up) to Tokyo.” Mahito’s future isn’t concrete, but we can be sure that his life will be full of opportunities, opportunities to grow and love and cherish the life he has, just as full as the opportunities for loss and grief.

Miyazaki’s films have happy endings. But a lot of the time, they’re not happily-ever-afters; there’s still work to be done. Nature is healing in Princess Mononoke, but the people living in it have to rebuild a new society, unclouded by hate. Kiki finds herself fulfilled from finally getting a handle on her delivery service. Even Ponyo, one of Miyazaki’s most lighthearted films, leaves the entire town flooded. And yes, Chihiro, having learned valuable lessons from her time in the spirit world, will have to carry them for the rest of her life. It’s strange, The Wind Rises feels so much more like a swansong than Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka would ever be, but I found myself thinking about this one a lot more. Perhaps it’s because it feels like Miyazaki at his most vulnerable and personal, even with how obtuse it can be sometimes.

How do you live? It’s a question that I’ve known for a while, I know it all too well. Miyazaki offers an answer in his film, and it’s consistent throughout his career. I’ve had an answer for most of my life, but perhaps the important thing isn’t knowing the answer to that question. It’s about what you do in the face of it, as the question looms large, floating forever until it won’t matter anymore, until there’s no one left to ask or answer it.

I’ve never thought about death as much as I did in 2023. I’ve thought about death. I’ve thought about dying. No, not in any sort of way that anyone should be concerned about really. It’s always in a more pragmatic, perhaps academic sort of way. “What if this terrible thing just happened tomorrow?”, “what if I had a heart attack right now?”, “what if I just didn’t try anymore?” that sort of thing. Yes, I do get stressed out about this sort of thing from time to time. My mind has found itself gravitating towards other voices, people who have death on their minds too. I’ve had at least two albums with sad, tired people singing about death unflinchingly on rotation in the past year. Sometimes I just want to be laid to rest, sometimes I just want to let it all go.

If nothing else, I love Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka not because it offers an answer to the question, but a glimpse into the mind of someone who has firmly answered it all his life, firm in his resolve, and yet, perhaps in the face of all that’s wrong in the world today, this time he just seems tired. Like a wildly-distantly-related granduncle, he tells me to cherish my relationships with my loved ones, to hold fast to these connections old and new, as if there’s nothing else that can possibly belong to you in this world. He tells me this earth is all that we have. He reminds me, anything worthwhile in this life takes work, and that I have to put in the work myself, but I’m not alone. He’s told me all these things for most of my life. And yet this time, it feels like he really wanted me to remember that. And maybe this time, I really needed someone like him to remind me. Perhaps the most generous thing Miyazaki could ever do for all of us is make every film like it’s his last. And as it turns out, Kimitachi wa Dō ikiru ka isn’t supposed to be his last film. He’s already buzzing with ideas for his next project; apparently, they can’t stop the man from working. And why would they? There’s still work to be done.