The Sunday matinee before Labor Day seemed as good a time as any to watch Shang-Chi, and so at one o’clock that afternoon I sat alone in the dark sanctity of the cinema for the first time in over a year and wondered about the film with cautious excitement, that now-all-too-familiar Marvel Studios fanfare heralding the coming of Hollywood’s first Asian superhero film.

A little over two hours later I came out of that theater and morosely walked the whole way home with a weight strapped to my chest, thinking to myself and wondering why I wasn’t happier about what I’d just watched. After all, there was a lot to love about the film, and I’d expect nothing less when Disney and Marvel Studios has so clearly and adamantly reminded me of my status as a member of the target audience; perhaps the feeling I had was that of someone being aimed at down the sights of the proverbial gun.

Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings has a lot going for it. Maybe you’re like me, becoming increasingly wary and perhaps a little jaded of how massive and unignorably relevant these Marvel films have become, and so you might know that it’s an equally massive compliment from me when I say that at times throughout the movie, I found myself forgetting that I’m watching a film set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Funnily enough, the moment this felt the strongest was the very first shot of the film. We’re shown the flag of the eponymous Ten Rings and under it, subtitles approximate the spirit of what the Mandarin Chinese-speaking narrator is communicating to her audience, introducing Tony Leung Chiu-wai as Xu Wenwu, the antagonist of the film. Discomfort was palpable among some of the other moviegoers around me when this was all going on. Make no mistake, the choice to exposit and express the table-setting of our story in Mandarin, the dialogue in Mandarin, the centering of a world-class actor from Hong Kong speaking Mandarin as the focus of the narrative for a not-insignificant extended period of time before finally, subtitles aren’t required anymore—this is all as deliberate as it gets. I couldn’t help but feel this sense of relief when I witnessed this, even as I took in the surreal totality of watching the artfilm heartthrob Leung I previously knew absolutely decimating an ancient army with CGI mystical glowy ring-bracelets. The following wuxia fight scenes between him and Fala Chen as Ying Li, appropriately operatic, feel similarly respectful of the gravity of what the film is trying to offer here: a genuinely Chinese action film experience, made in the USA.

When we actually end up in the US, Shang-Chi quickly tears off the mask and reveals itself once again as the Marvel film it is, Awkwafina’s Katy screams from the driver’s seat of the joyride BMW to remind me relentlessly that this is a film that doesn’t take itself too seriously, for better or worse. Awkwafina here does well with what she’s given, but she definitely feels much more “Crazy Rich Asians et al. Awkwafina,” and less “The Farewell Awkwafina;” frankly I was hoping that we’d see less of the former. Still, when the film introduces Simu Liu as Shang-Chi—or Shaun initially—it takes care yet wastes no time to present hallmarks of the Asian American experience: Shaun and Katy live in San Francisco, the film makes it a point to show Shaun taking off his shoes before entering Katy’s family apartment, they have congee for breakfast around the table as a family, and Katy’s mom and grandma nag at Katy and Shaun about careers and marriage, respectively. They enjoy late night sessions of karaoke now and then. The scene of the family having breakfast in particular—while incredibly brief—is executed in a way that’s right at home with the countless other films in Asian cinema (a recent excellent example being the aforementioned The Farewell) that highlight the cinematic quality of cadences and conflicts carried out at the dining room table, and writer-director Destin Daniel Cretton and company also take the time to plant some thematic seeds with Katy’s grandma musing about her late husband.

From here, the film picks up the pace as we get large chunks of Shang-Chi’s action, once again quite respectful of the Asian cinematic giants that came before it. In the fight scene on the Muni bus, we see Shaun wearing a bright sports jacket to contrast him clearly and legibly against the funerial black outfits of his pursuers. We get some longer takes (at least by Hollywood blockbuster and certainly Marvel movie standards) to show off some fight choreography, and a willingness to use the environment like railings and poles on the bus as a way to enhance the action. This all might seem self-explanatory for good action scenes, but you’d be surprised at how bad Marvel movies are at stuff like legibility and presenting the action in a way that’s easy to follow, fun to watch, and full of stakes. It goes without saying that the action in a film about a comic book character inspired by the likes of Bruce Lee and Jackie Chan would try to emulate those sorts of action films, but it wasn’t a given that Shang-Chi would actually pull off fluency in the language of its martial arts inspirations, so I’m glad that the effort was made and was largely successful.

Growing up as a starry-eyed moviegoer in Hong Kong, it goes without saying that I watched a good handful of Jackie Chan films as a child. Sitting in the cinema now in 2021, I feel my mind joyfully racing back to those simpler times and I see Jackie Chan in Shang-Chi, the way he utters that iconic line from Rush Hour, “I don’t want any trouble” in Mandarin, fighting with a Keaton-esque slapstick rhythm and using everything around him including his own clothes to fight; the fact that they’re fighting on a bus and he even hangs off the side of it at one point ties up the Chan allusions with an homage to one of Chan’s many world-famous stunts in Police Story. You’ve got Shang-Chi as Bruce Lee in the way he performs Lee’s Jeet Kune Do, the way he intercepts his foes’ attacks, that shot of him preparing to fight all of them with that stoic stance, the way he launches himself at one of them with a leaping side kick. You’ve even got Shang-Chi as Oh Dae-su from Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy, outnumbered yet not outmatched, fighting through the “hallway” of the bus in a longer horizontal tracking shot as he brawls through the entire gang of Ten Rings thugs trying to swipe his mother’s pendant from him. This dedication to allusions and retrospection toward landmark Asian action setpieces continues when Shang-Chi fights his way out of his sister Xu Xialing’s underground fight club in Macau, fighting ninjas atop bamboo scaffolding lining the outside of a skyscraper.

But action alone, crafted carefully and deftly as it is, can’t carry this film. At the heart of Shang-Chi is a familial drama between him, Xialing, and his father Wenwu. Watching Wenwu’s grief and inability to cope with the loss of his wife Ying Li is surprisingly poignant; as far as motivations for movie villains go, “Boo-hoo, my wife that completed me is dead now… guess there’s nothing left for me to do but some bad stuff” is a well-trodden road taken by way too many screenwriters, but he’s at least smartly characterized in a pathetic sort of way than most instances of this flavor of villain. It also helps that Tony Leung sells this narratively bankrupt concept so hard with his performance that there was nothing to do but be invested in the sheer emotion and gravitas he brings to every moment he’s onscreen. Wenwu has simple and straightforward goals at any point of his development in the film, but Leung injects so much nuance in his mannerisms, the way his face and blocking shifts and morphs to precisely express brilliant hopefulness or crippling regret, callous anger and petty accusation, fatherly disappointment and fatherly pride—I knew Leung wasn’t going to phone it in even in a Hollywood blockbuster, I just didn’t know how right I was going to be!

When he tells his children that their mother is calling to him to free her from Ta Lo so they can be a family again, Leung utters this line with such pathos and yearning, such a genuinely delivered line positively dripping with heartache and misplaced hopefulness. I think about moments like these and how moved I was in the theater, and it’s so clear that sometimes the simplest desires are the ones that drive characters with depth; sometimes less is more. I suppose this doesn’t really come as a surprise to anyone who’s ever watched a movie with Tony Leung in it, though. The man could be like, “Did you eat the lunch I left in the fridge? I specifically left it there with a Post-It signed ‘Tony Leung Chiu-wai,’ Come on!!” with those devastating eyes and I’d crumble and crumple up on the floor like discarded trash and apologize immediately with profuse sobs.

…A-anyway, another way to enhance Wenwu’s otherwise trite character motivations is to pit the villain against his own flesh and blood, and create considerations and complications around what his obsession is doing to his family. But that’s just the problem for Shang-Chi: how do you stand toe-to-toe with Tony Leung in a movie that is also (perhaps unintentionally) so much more invested in the antagonist’s anguish and emotional arc than those of the protagonists? Cretton has gone on record saying that after they developed Wenwu as a character, when asked who he wanted to play the part, he said he wanted Tony Leung Chiu-wai; the part was made for him. Shang-Chi continues down that fascinatingly uneven path laid down by Marvel’s own Black Panther where the villains are more interesting, more sympathetic and hotter than the protagonists, primarily because the screenplay itself doesn’t seem as interested in the protagonist’s wants and goals as it is in the villain’s motivations, their rise to power and their downfalls, and what all of this means for the viewer. There’s nothing wrong with Simu Liu’s performance, really; he does a good enough job playing a sensitive yet guarded Shang-Chi, and Meng’er Zhang plays an absolutely convincing portrait of someone essentially cast aside by her family to fend for herself, Shang-Chi’s sister Xu Xialing. Performances aside, the screenplay doesn’t take enough steps to highlight Simu Liu’s Shang-Chi as a character to relate to, or even the character the audience should aspire toward, and realizing that is what finally helped me make some sense out of my solemn mood walking out of the cinema on Sunday.

As much as I wish Awkwafina were cast in more roles that would bring out performances like the one in Lulu Wang’s excellent The Farewell, at least her character’s ultimately more relatable than Shang-Chi because her struggle is so keenly Asian American. Katy doesn’t have a white-collar job and it’s clear that her mother’s disappointment in her is an ongoing discussion at the dinner table. She doesn’t really know what she wants to do with her life but she knows she wants to enjoy it while it lasts. She’s out of touch with her own heritage; based on the conversation between her and Shang-Chi on the plane, she wouldn’t even be able to pronounce the film’s title because her Chinese is so rusty. It didn’t take long to notice that language plays a particularly interesting role in Shang-Chi, and my mind became a river running rampant with wild expectations about the film’s potential.

Later at the Macau underground fight club, the club’s master of ceremonies Jon Jon recognizes Katy as the bus driver during the Ten Rings’ attack, and notably his Chinese isn’t subtitled only when he speaks to her to emphasize the fact (and perhaps her embarrassment) that her Chinese isn’t so great, and she stammeringly says so to Jon Jon. He glibly replies with “Don’t worry, I speak ABC,” which probably sounds like a silly way to say “English” if you’re white but what he’s really saying is “Don’t worry, I speak American-Born Chinese,” which can honestly be a little derisive sometimes—take it from someone who’s actually been casually called “whitewashed” by a fellow Chinese classmate before because of something as asinine as being bad at math as an Asian, a real banger from the Now That’s What I Call Internalized Racism Greatest Hits album. These little moments with Katy and her unspoken wrestling with her heritage, they’re potent complexities for her characterization, tiny complications the film made a point to present to the audience. All of these aspects of her place in this narrative, these conflicts, they’re all representative of so many Asian Americans’ experiences; that is to say, her character conflicts are relatable because all of it is concrete.

Weighing Shang-Chi with the strengths of his sister Xu Xialing’s own narrative arc also doesn’t do him any favors. Estranged by her entire family after her mother’s death, Xialing spent her childhood secretly teaching herself the skills she needed to become truly independent and run her own operation; in effect, Xialing has for the most part already achieved a lot of her character growth prior to the present day of the film’s events. This might sound like I’m saying nothing happens to her, but it’s actually her consistent presence as a formidable force holding true to her own ideals and desires that makes Xialing so compelling, what makes her human.

Everyone who watches Shang-Chi will remember Xialing’s introduction because it’s so charged with history and tension. We don’t need to know what was done to her to know that when she’s in the ring with Shang-Chi, he must’ve really fucked up. Giving her brother the silent treatment while he begs her to listen, Xialing wordlessly conveys this profound sense of betrayal and bottled rage through her every strike, visceral and true. When she finally seems to listen after Shang-Chi mentions their father is pursuing them, we see a flashback of Shang-Chi promising to come back for her in three days, we see the thoughts running through her mind as she strikes him down with such righteous anger that we’re the ones in the fight club cheering her triumph; we’re Katy, betting on Xialing instead of her best friend. Time and time again in the film, we’re shown the fruits of Xialing laboring on her personhood and her skills, we see the actualization of her character right away in the ring, and in flashbacks we see how she got there.

Maybe it’s because of how the screenplay allows for Xialing to continually prove herself and confirm who she’s become, maybe that’s why Shang-Chi as a character feels so flat. For Shang-Chi, it felt as though the writers had a few options for what his central conflict could be but when it finally came time to choose one, they decided on one that felt the most reactive, not proactive. That is to say, it doesn’t really feel like Shang-Chi really ever takes charge of his life in the same way that, say, Xialing does. That’s not inherently a problem with writing a character, let alone a protagonist. Some of the best protagonists start out or even spend most of an entire story being this way; I’m not saying you can’t make a film about a flawed character. The problem is the film almost acts like it can’t decide if it likes Shang-Chi having flaws or not, it doesn’t really bring them to our attention or elaborate on why it’s important for him to overcome these flaws, and that’s a critical mistake to make in a movie about a superhero.

What does Shang-Chi actually struggle with in the film, what are his flaws, and how does he overcome them? The next weekend I went to see Shang-Chi again with my roommate to find an answer to these questions, and while I think I had a firmer idea of the writers’ intent behind Shang-Chi’s narrative arc afterwards, I also now clearly understand why I had a hard time tracking Shang-Chi’s character motivations the first time around.

Is it a feeling of being alienated from his heritage? We’d just assume with how close and tight he is to Katy that Shang-Chi has a similar Asian American experience growing up; based on the brief story on how they met, where he mentions not really speaking English that well and being made fun of when he was in school, he kind of does. But it’s also complicated and mired in a troubled past that involves supernatural parents, shadow organizations carrying out assassinations, and intense abusive combat training. It’s evident that Shang-Chi does have a stronger connection to his heritage through the way the film presents his fluency of Mandarin compared to Katy speaking in English; it makes sense given the fact that he fled to the States when he was fourteen according to the film. Because America also represents a safe haven from the Ten Rings and his past, Shang-Chi deflects and suppresses this connection somewhat as a means to distance himself; he’s Shaun, not Shang-Chi at first.

Shang-Chi highlights this moment of Katy and Shaun talking on the plane ride to Macau about how Shaun is not actually Shaun but Shang-Chi. As I mentioned before, I think Shang-Chi as a film up until this point does a pretty good job at treating the runtime with economy, not wasting too much time and only having a scene if it matters to the narrative. And it’s because of this economy that I expected something greater to come out of this conversation. Not only was this a nice way to actually educate the audience about how to even pronounce “Shang-Chi” without pulling up some PowerPoint slides, I felt like they were setting up this idea of names as something that carried thematic weight, representative of Shang-Chi’s past and maturation toward a fully-realized character. Maybe he has a hard time deciding who he wants to be, maybe he rejects this heritage, and that’s subconsciously why he rejects his Chinese name. Ultimately it was a missed opportunity that never paid off by the end of the film and this is something that really bothered me about Shang-Chi. At least, I think the fact that we as Asian Americans tend to have an English name and use that instead of our native name is something really interesting to think about and interrogate in a film, and it’s disappointing that Shang-Chi comes so close to doing that within the context of an expensive mainstream blockbuster movie, yet doesn’t really go through with it.

I know if I were a child living here in America and Shang-Chi came out, and it gave me some sort of closure or perspective on what to make of my several names, I’d have found refuge in the fact that other Asian Americans like me experience the same anxieties, the same pangs of shame and the same bouts of yearning to be proud of who I am. I spent most of my time in grade school dealing with situations where my “English” name and my Chinese name would both be met with confusion at best. Anyone who knows me from my time in grade school back then knows that I didn’t go by my Chinese name at first; I went by a name my parents had chosen from the Bible (my parents were missionaries and my dad’s a pastor). The real kicker here is that instead of the milquetoast Christian names like your Steves and your Matts or Johns and what have you, my parents chose “Zichri” as my first name, a Hebrew name so obscure in the Christian Bible that you’d have to tirelessly skim through those genealogies everyone skips to find it. Either I or my parents decided that we’d pronounce this name as something more like “Zachary” later on out of convenience, but it annoyingly stayed “Zichri” on documents and paperwork and such that eventually when I had to register to a different school in the same district filled with people that’ve never met me before, I had to decide if I wanted to have my Chinese name instead, and I ran with it. Even then, I’d be met with questions like “why can’t you have a ‘normal name’ like everyone else?” even when “Ming” is infinitely simpler to pronounce and remember than something that doesn’t really roll off the tongue rendered in English.

While Ming Dao [銘道], my Chinese name, was still chosen by my parents to carry a decidedly Christian weight according to their own personal etymology (I can awkwardly approximate Ming Dao as something like “God, committed to memory” or even “the Way [back] to God, never forgotten” if we decide to take the Dao [道] in Ming Dao to mean more like a Christian “Way” or logos over the Dao in Daoism, feel free to correct me if I’m wrong, Mom and Dad), after I left the Church, there was a part of me that retrospectively found this decision to almost reclaim my Chinese name fitting and liberating, like it was an act of agency committed many years before I knew what I was leaving behind, freeing myself from the then-unconscious shackles of parentally-inherited religious dogma, post-colonial anxieties, and even gender by rejecting an astonishingly specific and obscure “Judeo-Christian” first name. I can’t speak for anyone else, but I think I wouldn’t be too off the mark if I ventured to guess that other Asian Americans have had similarly elaborate stories to tell about something as simple and ubiquitous, something as central to one’s personhood as a name.

Really the only time this topic of names comes up again in a blatantly meaningful way in Shang-Chi is when Shang-Chi, Xialing, and Katy have dinner with Wenwu, a sort of rhyming inverse to the scene where Shang-Chi and Katy have breakfast with her family; Wenwu speaks about his late wife similarly to how Katy’s grandma grieves her late husband, but Wenwu’s unwillingness to accept his wife’s death is decidedly different to Katy’s grandma honoring her husband’s memory. Again, this parallelism illustrates a structural strength of Shang-Chi’s writing that the MCU could probably see a little more of. What stuck out to me more in this scene is how Wenwu finally introduces himself as Wenwu in the film. He asks Katy for her Chinese name, and while he does this with a precisely palpable sense of condescension, he then gives a salient monologue about how sacred names are, how they connect us to those who came before, and even throws in a dig at how Iron Man 3’s version of “The Mandarin” (Wenwu is an adaptation and subversion of this comic book character as well as the wildly insensitive orientalist character Fu Manchu) and the Marvel continuity at large appropriates and clumsily creates names out of ignorance. And so, after this scene I started wondering—my cup runneth the hell over, all over the showroom floor with hopeful optimism—if this is truly part of some sort of thesis of the film.

But then we actually get The Mandarin going by the name Trevor Slattery here from Iron Man 3, reprised by Ben Kingsley in the film, a comic relief character once again cutting through any sort of thematic tension like a blade. While there’s something to be said about this former appropriator accepting his real name, embracing his old passion of acting and being turned into this likeable butt of the rest of the film’s jokes, and I’m glad that Ben Kingsley got to have a lot of fun with this role, I also couldn’t help but question how necessary it was even if it could tie into this loose narrative thread of names somewhat; it just felt so distracting. It’s also around this point that the film starts to lose a lot of its momentum.

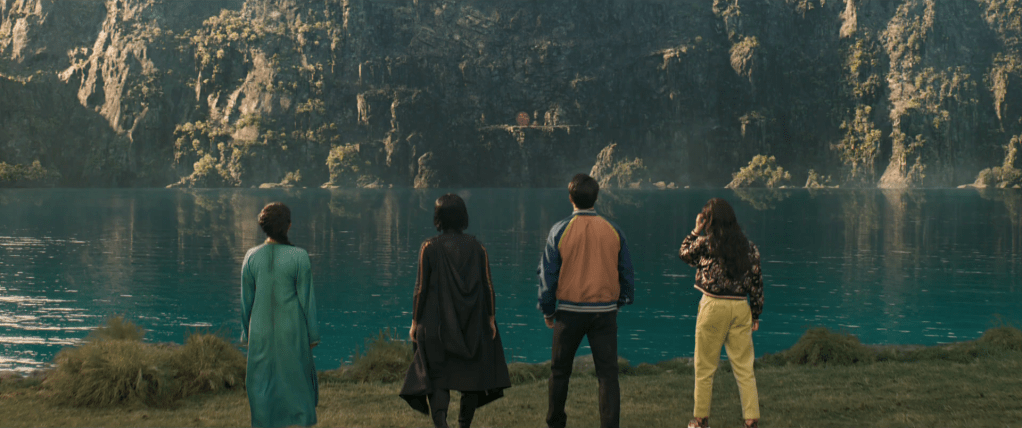

Riding in an decaled SUV that looks like it would fit right into Need For Speed: Underground 2 if it were made today, Shang-Chi, Katy, and Xialing reach the mystical realm of Ta Lo, filled with traditional Chinese mythological creatures such as qilin (that chimerical dragon-horse thing that does the Princess Mononoke shishigami stare), hundun (the little winged chubby furry ball creatures, one of which Trevor has named Morris), fenghuang (somewhat analogous to a phoenix in Chinese mythology), huli jing (those nine-tailed foxes. They’re not Pokémon, okay?), shi (those hulking guardian lions), and a guardian dragon known only as The Great Protector.

As spectacular as all this is, I feel that it is precisely Ta Lo’s fantastical nature, its mythology and its reverence to traditional imagery that plays a part in a lot of issues tying up Shang-Chi’s narrative and themes, and I don’t just mean its artificiality because of how most of it is green-screen trickery, though this certainly doesn’t help. The gang rolls up to Ying Li’s village where we meet Ying Nan, played by Michelle Yeoh. She acts as a historian of sorts for Ta Lo to both the Xu siblings and the audience, and it’s here that we finally understand who is manipulating Wenwu into thinking his wife is still alive. Telling the story of Ta Lo’s people and its culture through a beautifully rendered wood carving, Ying Nan gives us the slightest glimpse of Ta Lo as a highly advanced civilization before revealing its greatest enemy, Dweller-in-Darkness. Unsurprisingly, after the film I had to look this up.

Dweller-in-Darkness is apparently a wacky Cthulhu-esque entity usually more associated with Dr. Strange’s rogue gallery. Turns out D-in-D’s whole schtick in this movie is being adapted into a trapped mindflayer-dragon sort of thing that can communicate and tempt people strong enough to free it by offering their deepest desires. I don’t find Dweller to be a particularly strong candidate for the mastermind behind the plot of Shang-Chi because it doesn’t enhance the relationships and conflicts that the film is already centered on. There’s only one advantage to a villain like this and it comes with a whole host of disadvantages common to the MCU that we’ll talk about later.

Aside from this, one might posit that there’s something to be said about how this entity and its soul-sucking minions are from a different Marvel mythos entirely. They might argue that perhaps, Dweller-in-Darkness serves as a sort of analogue to something like a foreign power encroaching on an Eastern realm and crippling its development by asserting its influence. I’ve certainly given this some thought and ultimately, it’s the same problem with something like Slattery where I don’t think the film really goes far enough if this was intended to be some sort of allegory or representation of Westernization or imperialistic foreign influences. There’s a lot of potential here as well, but like the loose thread of the importance of names, this aspect of D-in-D is half-baked.

It’s especially disappointing because Ta Lo as a representation of “an idealized, culturally Asian space” deeply bothered me upon closer examination. Forgive me for bringing up Black Panther in relation to this film again, but it seems obvious that Marvel Studios themselves wants us to view Shang-Chi in some ways as “Black Panther, but for Asians,” as awfully reductive as that sounds, but let’s play along for now. Aside from blatant similarities such as its being closed off from the rest of the world, and possessing a sort of technology or tool that gives them an edge compared to other cultures (The Great Protector’s dragon scales), Ta Lo presents to us a realm unfiltered by foreign influences, and it thus presents its people as living harmoniously. But unlike the glorious afrofuturism of Wakanda, Ta Lo is decidedly traditional and mythical—it looks backwards, not forwards. It isn’t simply removed from the societies of the world at large; it is another world, another dimension entirely. It does not imagine an idealized past, present, and most importantly, future of Asians thriving the way Wakanda does representing the African diaspora, but chooses to relish in folklore and fantasy. The fact that our heroes are supposed to fully realize themselves here, in this dimension removed from “the real world” feels troubling to me.

In any case, our heroes all undergo a sort of contemplative moment in Ta Lo, where each of them experiences some sort of breakthrough in their development, or begins to see a better path forward. At least, for Katy and Xialing, they do. The film has firmly focused Katy’s arc towards her anxiety around committing to a lifelong discipline or passion, and here she finds some direction when she trains to be an archer, and eventually works hard enough to let loose a deadly blow on Dweller-in-Darkness by the film’s climax. Xialing on the other hand doesn’t exactly become stronger per se, but she finds a healthier way to focus her strength. She isn’t training to surpass or overcome out of spite anymore; as Ying Nan says to her, she is training “as [an equal]” now. It’s funny that we don’t really see her training communally with the others in the village despite this line but we’ll just pretend that she does that off-screen like the film has us doing a lot more than I’d like…

I think it’s pretty telling that maturation and a clearer sense of direction comes more naturally for the women in Shang-Chi’s life. I know that Cretton and screenwriter Dave Callaham have mentioned that they wanted to ensure that the women in this film are treated with humanity. While that bar sounds incredibly low, it also rarely has been met by Hollywood films featuring Asian women until much more recently, so I can do nothing but applaud the effort here. I also think this perhaps could be somewhat of a slight on our protagonist Shang-Chi, because while his best friend and his sister find direction they carry into the climax, Shang-Chi only seems to be taught a lesson, yet ultimately falters going into the final confrontation with his father and the Ten Rings. Narratively, I can tell that the writers wanted to throw one last curveball into the mix to create some tension and doubt for an exciting ending, because it’s here that he tells Katy and the audience that he did in fact kill his mother’s murderer like Wenwu tasked him to.

It’s here that the film drives home Shang-Chi’s conflict for the audience: Shang-Chi, in spite of all his attempts to run away and suppress his past, is a victim of his father’s harsh upbringing, and he is becoming like his father in the worst way possible. The film makes this concrete through implications of murderous intent. Earlier in the film, when facing off against his former instructor in Macau, Shang-Chi gains the upper hand after an explosive display of hand-to-hand combat. We’re then shown flashbacks of him as a child and a younger man, taking much abuse from this masked ninja, and it’s being communicated to us that Shang-Chi’s resentment is boiling over as the images become almost overwhelming, and he nearly plunges a knife into his assailant until Wenwu stops him. This is, visually, a strong moment that foreshadows the later revelation that Shang-Chi lied to Katy and did in fact assassinate the leader of the gang responsible for killing his mother.

There are a few problems with the way the film handles Shang-Chi’s characterization here. For one, this previous scene I just mentioned and labeled a strong foreshadowing moment for him, this is really the only time we get some visual hint at Shang-Chi actually being a killer. Aside from this, we have very little reason to believe that he would be lying to Katy about his past again. There is absolutely no tension about this, and practically no development about Shang-Chi himself for most of the film until this gets brought up again. The film provides a strong sense of where Shang-Chi came from with its frequent flashbacks but there isn’t enough that he does in the present that really gives me the impression that he might ever go back to that life, or learn the wrong lessons from it.

You could argue that the film refraining to tell the audience until this very moment right before the climax is a strong way to deliver information to the audience on a need-to-know basis for maximum effect. But there’s the other problem: when Shang-Chi reveals this truth to Katy, we’re shown a flashback, but nothing visually striking to represent the murder had occurred. The first person ever to speak the age-old adage and perhaps cliché of “show, don’t tell” is screaming from the void right now; they’re spinning angry cartwheels in their grave. The worst part about this is the film already gave us an image to grab onto in a previous flashback: Wenwu handing over a dagger to his son. Despite the terribly dark lighting of the scene, a father handing a dagger to his son, effectively the handover of a legacy, is a very powerful image. When Shang-Chi reveals that he actually killed with it, we could’ve been shown something, anything, but instead we simply have to imagine it off-screen. I’m thinking something like that dagger, covered in blood, falling to the floor as a young Shang-Chi realizes and regrets what he’d done, a son impulsively rejecting Legacy itself in terror. Anything would’ve sufficed. Fortunately, the image of a father handing over a Legacy to his son pays off in a different way later, but more on that in a bit.

One sloppy oversight as well is this fact that Shang-Chi has lied to Katy twice, yet nothing really ever comes of it; we aren’t being shown any consequences of the supposedly flawed things Shang-Chi has done, so why should we care? Sure, Awkwafina gives us a pretty convincing performance of a Katy hurt and concerned for her best friend. I was briefly concerned myself: Was this going to lead to some hang-ups or some issues right before the final battle? Will their resolve be shaken just when it needs to be the strongest? Not really, they seem to be in tip-top shape when the Ten Rings arrive. Usually following a moment like this, a story would have situations where these friends would bicker or harbor bitterness, create greater tension, and we the audience would be riddled with anxiety, “Aiyaaaaaaaa stop fighting amongst yourselves!” We’d say. There’s absolutely nothing like this here.

There’s even a moment where Katy resolves to fight. She defies her instructor’s insistence of her inexperience, picks up a bow, and declares “Sorry, I have to help my friends.” Wouldn’t this line ring so much truer if she had just bitterly lashed out at Shang-Chi, fed up with all the lies and secrecy and confusion about her best friend? Could she even call him that anymore? When she takes that shot at Dweller-in-Darkness’ throat, wouldn’t we feel so much more nervous and then later triumphant about it if we knew she was still harboring resentful feelings toward Shang-Chi, feelings that she sets aside in exchange for belief in her best friend and supporting him? The film is so close to getting these things right, so tantalizingly close to stirring up emotion and just drops the ball here.

This all goes back to hamper Shang-Chi’s characterization. Again, we don’t see enough consequences for these flaws, these mistakes he makes; he doesn’t make a whole lot of them either in the present day! Really, it’s like his character effectively takes a backseat until his training with Ying Nan, and this very moment where he and Katy talk about his past again. Everything that happens in the film that involves Shang-Chi, it happens to him, at him; that is, he doesn’t make these things happen due to some goal or some force of will or anything like that. He always reacts. He gets told things, gets manipulated to go places, gets stuff like his superhero outfit handed to him. Everyone around him seems to do the opposite. Xialing is always charging towards some goal, proving herself, seizing what she believes is owed to her. Wenwu drives the entire film’s plot forward because of his sole desire to see his wife again. Even when Shang-Chi meets the Great Protector, it’s almost like he stumbles upon her. He comes to a realization about how his family needs him only after the Great Protector was already raring to go, bubbling from the depths of the river. What, was the dragon going to just let the guy drown?

The only thing that really saves this final showdown between the Ten Rings and the villagers of Ta Lo are the performances, and even so the sequence falls short in a few ways. Courtesy of Tony Leung’s Wenwu, we get this metal-as-hell line where he calls this old guy a “young man” and says that he’s lived for many lifetimes over, and there’s a lot of tension brewing, but ultimately while there’s still some solid action here and there, we regress from bona fide martial arts action on the bus to less practical, CGI martial arts action in Macau, to a lot of CGI in the finale, and it gets worse later. What struck me is while it seemed like there was a chance for both Michelle Yeoh’s character Ying Nan and Xialing to trade a few blows with Wenwu, we never get to see this, and this feels strange to me. Particularly, I’d imagine Xialing would like to exchange a few words over a session of fistfighting with the father that ignored her the entire time since her mother died, but for some reason she defers this honor to Shang-Chi while she contends with Razorfist, which is a lot less interesting.

Fortunately the confrontation between Wenwu and Shang-Chi is thrilling and more importantly, emotionally-charged and turned up to eleven. For a brief moment, I forgot the fact that Shang-Chi didn’t really get much time to develop enough to really deserve such a fateful bout with his father; the tension and the delivery of the lines between them sold it well enough. Leung as Wenwu is so menacing here, twisting the knife with such hateful frustration and seething anger, while Shang-Chi straddles the line between being shakily outmatched and furiously relentless in the way he fights back with the dragonscaled staff he wields, yelling “is this what you wanted?!” at his father in this almost childish, jockish sort of way that really works. When he gains the upper hand and strikes Wenwu down, the pettiness in the way Liu delivers the line, “Even if you could bring her back, what makes you think she’d want anything to do with you?” hits like a truck hurdling down a highway. By the time I saw Leung as Wenwu showing genuine reflection on his face over what his son had just said, I was a wreck. Wenwu’s silent answer to Shang-Chi’s remark in the form of a vicious blow to the gut, sending him into the river with such force that it rips it apart, boomed louder than several trucks hurdling down that same hypothetical highway.

It’s a shame then that we couldn’t really get this same intensity at the Dark Gate, where Wenwu inadvertently frees Dweller-in-Darkness. While some of the ways the Ten Rings are used in combat are pretty imaginative, I can’t say I’m as thrilled about the two of them trading rings and flinging them around a ton, especially now that the environment around them is so muddily grey. When Shang-Chi finally accepts himself as a product of both his father and mother and embraces both of them as part of who he is, he defeats Wenwu and instead of killing him, gives over the Ten Rings back to his father in an act of pacifism. When the Dweller-in-Darkness is freed and I saw the form it took, I immediately grumbled to myself.

As I noted before, there’s only one good thing about Dweller-in-Darkness’ role in this narrative, and that is it provides Wenwu with a chance to redeem himself without condoning or absolving him of his past wrongdoings. Wenwu is immediately restrained by Dweller’s tendrils and as he looks down at his son, we see a montage of him looking down on his son throughout his life, backwards through time until we see that image we saw before, of Wenwu holding his baby son in his arms. We can glean this sense of trust, perhaps pride in his son in that brief moment, and we see him relinquish his Ten Rings from his arms to his son’s. Wenwu once again passes on his Legacy, his family, to his son, trusting him to get the job done, before his soul leaves his body. As far as visual storytelling goes, I’d call this a home run. We feel the gravity of this final act from a father to his child, and there’s a profound sadness that comes with watching him die right afterwards, but it’s also what he deserves, it feels right. When it comes to bad dads in the MCU, I’d say it gets a score of “(Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 + 1) out of ten.”

To continue the baseball analogy, after this home run, we get to slog through an entire boring inning’s worth of CGI slop. Have you ever actually sat through an entire major or minor league baseball game in a stadium before? Maybe you were a child just sitting there in the stands, watching silently, and maybe you were sipping Coca-Cola through that long and winding plastic straw and nomming on some nachos, and then that epiphany dawns on you, the realization that nothing really interesting has happened since that one home run like, three innings ago, and you think to yourself, “hmm, I think I’d rather be home doing something else right now.”

Well okay, maybe that’s just me but the point is, I really wish they didn’t wrap up the movie with this blurry mess of a battle between a CGI dragon and another CGI dragon that looks more like a CGI Cthulhu-wyvern or something. Yes, the fight provides an excuse for Katy to achieve some sort of closure with her struggle to commit to something. Yes, it also provides a chance for Shang-Chi to prove to his sister that he is willing to stupidly risk something so final as unleashing an eldritch horror upon the universe as we know it to save her. But God do I wish we didn’t have to do all this while getting a migraine. I get that the scene has to feel ominous and bleak but blanketing the screen with just this grey all over is not doing anyone any favors. Once again, this is certainly not something that’s exclusively an issue with Shang-Chi; it’s something that basically all MCU films struggle with. I want to be impressed with what Shang-Chi does to kill Dweller-in-Darkness, but between the simulated camera shake and the incomprehensible CGI, I kept wishing that the fighting had ended after Shang-Chi and his dad wrapped things up, and I wished for something even further back, wishing we had anything remotely as kinetic and exciting as that first action scene on the bus at the start of the film.

That’s just the thing, it really feels like the start of the film, set in the “real world,” concretely centered around Asian American themes of cultural heritage and familial conflict and dealing with loss, it sets up and presents the audience with the promise of so much potential, yet Shang-Chi just kind of tapers out by the time the climax rolls around. We spend too much time in Ta Lo, we spend so little time seeing Shang-Chi being a hero outside of that, only seeing him use the Ten Rings to “Kamehameha” Dweller-in-Darkness as Katy puts it to their friends at the final scene before the credits. By then I couldn’t help but wonder if anyone else felt like Katy’s arc kind of just deus ex machinas itself into her “finding a passion or direction” for her life instead of her really choosing to do anything. I suppose it’s only natural that she and Shang-Chi get called to Kamar-Taj by Wong at the end of the movie instead of either of them choosing to go there or choosing to do anything themselves. Xialing, unsurprisingly, is the only one who has any sort of firm agency by the end of the film, as she gets to girlboss around her new primarily women-run Ten Rings, and we’ll probably get some sort of Disney+ show about her or she’ll be the anti-hero to Shang-Chi’s supposedly heroic self in a sequel film.

By now you might be thinking, “Wow Ming, you’re being really hard on this movie right now.” And yeah, I kind of am, undeniably so. At the risk of being a bit too on the nose, I’m being really hard on Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings the same way a parent watching a child growing up would be. That is to say, I love Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings. I love Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings but sometimes I don’t like it, because sometimes what it wants to be isn’t what I want it to be. Sometimes, it feels like the film is trying to impress me more than it’s trying to relate to me and tell me something valuable. Throughout the film, Shang-Chi checks things off of a list, fulfilling Asian hallmark quotas, and it’s here that I want to turn the totality of my compliments that I just brought up earlier in this essay on its head, and present the possibility to anyone reading this that yes, you can completely go in making a movie like this with the best of intentions and still not pave a way forward and even potentially reinforce different stereotypes.

What bothers me about Shang-Chi‘s good intentions is—with all its insistence on respectfully paying homage to The Greats, reclaiming problematic characters, and debunking stereotypes—in the end, at best, most of this doesn’t go hard enough and tease out its potential to actually service the film’s narrative and flesh out its characters. The loose threads about the importance of names, implications of rampant Westernization and foreign influences and invaders, reconciling the loss of our culture with how we synthesize new cultures in melting pots like America, it could all serve to make the film stronger emotionally as well as intellectually but what we get is something decidedly disconnected from its characters, the elements of the story that move it along.

In its worst cases, the references and even the attempts to shut down stereotypes or reclaim characters can feel aware of themselves in the most distracting way possible. The way I talked about a long list of Asian American hallmarks at the start of the film in San Francisco, and the mythological creatures when the gang first drive into Ta Lo, I list them off because the film presents them to us almost like checklists instead of peppering the story with respectful presentations of culture organically. I’ve seen people mention how they’re glad that Shang-Chi doesn’t simply end up a martial arts master when Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings comes to a close. Me too, but I’d be happier if the film actually showed him being the superhero he is outside of mystical Ta Lo after he inherits the Ten Rings. When we do see him being heroic for the sake of it on the bus earlier in the film, he’s a pastiche of martial arts movies. Wenwu is the most successful character from Shang-Chi when it comes to doing away with problematic characters, and even then, he’s more of an original creation than strictly a reclamation of an insensitive stereotype. Debunking a stereotype such as “Asians being bad drivers” by making Awkwafina’s Katy an actually astonishingly competent driver, why even give such an asinine stereotype the time of day? I’d be fine with this if she decided to actually become, as she put it, “the Asian Jeff Gordon” by the end of the film. You know, that would actually give her arc more closure than what she has right now, an archer in a mystical land… She would find success being a racecar driver instead of doing some sort of white-collar job, free from the weighty expectations of her mother. She loves cars, is so good at driving them that she navigates a literal shifting labyrinth of a bamboo forest, and has spent the whole film using this skill to help her friends in meaningful ways. Think about it.

When I got home from that Labor Day Weekend matinee and sifted through my thoughts floating and bobbing around in my head on the way, I realized that I kept asking myself, “If a Chinese kid, an Asian kid… if I were a kid and I watched Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings, would I be inspired to be like Shang-Chi?” And if the answer was “yes,” what are some things about him that I’d emulate? What qualities would I bring along with me for the rest of my life?

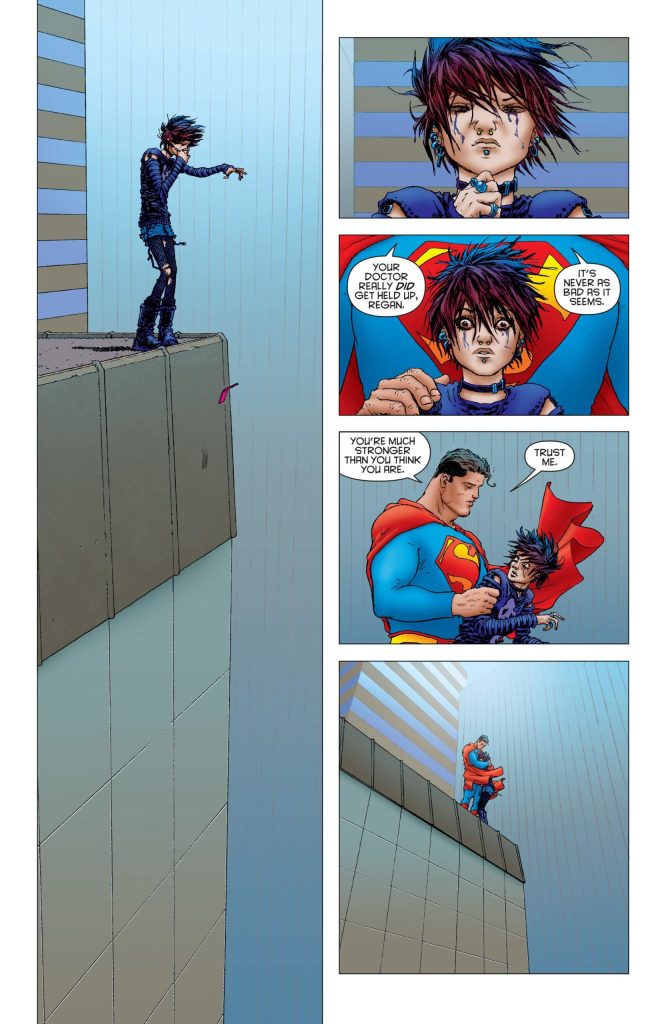

I’d say that my Christian upbringing made up one half of my moral compass as a kid growing up in Hong Kong and then in Midwestern America; the other half came from watching American superhero cartoons and movies—your Supermen, Batmen, Spider-Men…

It might be difficult to see it now—with superhero movies trying so hard to impress audiences to the point of their most ardent defenders waging online proxy wars against some villainous facsimile of Martin Scorsese in their heads decrying Marvel movies as “not cinema”—but a large reason why superhero stories are popular in the first place is the fact that they were inspiring ideals to strive toward. Superhero stories weren’t complicated and didn’t have to be, they just had to present a hopeful solution to humanity’s problems. This didn’t mean that the heroes themselves didn’t have depth to them, not by a long shot. In fact, it’s usually because of their simplicity that the depth of their character shone through.

Stop me if you’ve heard this before: Superman is a god among us, so powerful and purely good, and because of this Superman is unrelatable, has no depth, and is inherently boring. If you knew anything about the character written well, if you even knew as little as I do based on the few pieces of Superman media I’ve engaged with in my life, you’d know that this take is boring and dull in the same way that it seems to regard Superman. It’s precisely because Superman’s values and ideals are ubiquitous and central to his character that we realize what’s on the line when those values are tested by his opponents, the situations in his life, and unnatural causes. The unstoppable force to him as immovable object, Superman’s morals are set in unbreakable stone, and that’s why when it seems like the easy thing to do would be to make an exception, we as readers and as audience might find our eyes transfixed upon him with suspense-filled childlike fascination as he’s tempted to do away with those pesky morals and just kill someone or let a lot of innocent people die to accomplish his goals, and he overcomes these urges. Or in the case of recent Superman movies, you just see him kill someone or let a lot of innocent people die.

Superman always believes there’s a way to solve the world’s problems without the loss of life. Batman doesn’t kill, and he doesn’t use guns because his parents were shot in an alley one night. Uncle Ben tells Peter Parker that with great power comes great responsibility. These sorts of ideals are quintessential American myths, so ingrained within our collective pop cultural unconscious that we hold these truths to be self-evident, as American as apple pie.

You could argue that Shang-Chi shares these sorts of ideals somewhat, you can look at what he does in the film and say “see, he thinks killing is bad” and still within the context of the film itself, you have to wonder if the only reason why he doesn’t kill is more because it means he takes after his dad in a troubling way and less because he values human life. What’s so frustrating about Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings is honestly, I wasn’t expecting them to even attempt to meaningfully talk about stuff like the Asian American experience because I didn’t think something like a Marvel movie was going to do it well; while I was pretty hopeful for a little while there and I really do palpate the respect oozing from the filmmakers, ultimately I was still right. All I really expected of it was seeing an Asian person on the silverscreen, being heroic, caring for other human beings, setting an example for growing Asian kids. That’s all I ask of Hollywood’s first Asian-led superhero film, and it’s honestly not asking for much. Imagining myself as a child, coming out of the theater and somehow keeping a diary better than their older self, I can see myself scrawling on loose-leaf paper matter-of-factly, declaring definitively, “Shang-Chi does kung-fu. Shang-Chi does not kill. Shang-Chi loves his family,” my hypothetical multiversal childhood self apparently oblivious to the fact that in Asia, people can just be heroes without giving their best impression of Jackie Chan or Bruce Lee, making a heavy-handed Big Deal about the Importance of Family, or arguably wasting time retroactively apologizing for problematic characters made by non-Asians and reclaiming them in the process. Shang-Chi himself is someone this film is attempting to reclaim, after all.

There’s a moment in Shang-Chi where Michelle Yeoh’s character Ying Nan tells the Xu siblings that their mother set aside gifts for them, knowing that they would one day find their way to her home. The two of them unwrap the silken cloth to reveal dragonscaled cuirasses, and they spend a reflective moment looking at the Legacy their mother left behind. As the Ten Rings organization breaches the enchanted bamboo forest into Ta Lo, the villagers and our heroes gather their weapons and prepare for battle, and we see Shang-Chi unceremoniously appear in his new dragonscaled superhero outfit as they assemble to meet the Ten Rings. Seeing Shang-Chi’s first-ever appearance in what I would imagine is how he’d look for the rest of his time in the MCU really bothered me, not only because the outfit itself doesn’t pop at all in terms of color or design, but because it felt almost like the movie was too embarrassed to allow itself the fanfare or spectacle typical in moments like these.

I found myself in a state of cinematic reverie, seeing in my mind’s eye a more charismatic Shang-Chi, perhaps running fashionably late to greet his father on the opposite side of the battlefield. Perhaps someone, maybe Wenwu himself would ask where his son is, and Shang-Chi would appear in something vibrant and proud, not muted and understated, and the film would visually celebrate his arrival. Perhaps he’d struggled with who he was and who he wants to be going forward, wrestling with his heritage and up until then, suppressing it in an attempt to run from his past. Perhaps when he finally clashes with his father, all that he’d done in the film so far actually led up to this moment, and yet Wenwu would try to sow some doubt in him by reminding him of how he subconsciously rejected something as sacred as his given name, how he doesn’t even know who he is. And perhaps Wenwu would suddenly find himself blown back by an impressive counteroffensive, his son’s immense resolve and completeness of character shining through, and hearing him declare triumphantly, “I’m Shang-Chi, son of Xu Wenwu and Ying Li.”

Something as campy as that would feel right at home in a superhero film, and I mean that in the most affectionate way possible. I can’t help but wonder if Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings didn’t allow itself the grace and honesty it and its audience deserve, to allow itself to wear its hopefulness and desire to inspire on its sleeve. I can’t help but wonder if—in a post-Watchmen world where the alternate universe worst-case Superman is simply The Superman we’re left with in cynical, nihilistic interpretations of a literal embodiment of Hope—Shang-Chi felt like it needed to sophisticate and subvert, to present itself with nuance. To that I say, with how little representation we have right now, how much more we need to work towards, we’ve not the privilege to be subversive when we didn’t even get it right the first time.

Coda

On September 8th—apropos of nothing, I’m sure—I whimsically wrote “銘” next to “Ming” on my nametag at work and smirked regrettably at my calligraphy being wildly out of practice. I was taking a lady’s order during that Wednesday morning rush and I saw her eyes glance up from her phone toward my apron, and said to me in a voice teetering on a tightrope bridging the gap between performative and genuine:

“I like that you wrote your name like…” Here she ventured to gesture toward my nametag by barely lifting her hand.

“…that… It’s important.” And she gave the slightest of nods in affirmation; to me or to herself, I cannot say.

I think about this exchange every day. If nothing else, I’m inclined to agree with her.

– 雷銘道